New vaccine introduction is no small feat: it takes months of coordination, teams of people, and sometimes hundreds of miles before vaccines make it from manufacturing facilities to the communities that need them.

In the case of typhoid, the risk of disease is often higher among hard-to-reach populations without adequate access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene. Typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs) are a powerful tool to prevent the disease—but first they must reach the children who need them.

In this photo essay, we trace the journey of TCV from start to finish, highlighting the dozens of partners that work to bring TCVs to communities across the globe.

Research and development

The journey begins in the lab, where scientists conduct extensive research to ensure vaccines meet safety and efficacy standards. The research and development process involves clinical trials, regulatory approval, and effectiveness studies once the vaccine has been approved and is in use. World Health Organization (WHO) prequalification of vaccines is an extensive process that involves assessing all the available data on a product and inspecting its manufacturing sites to determine that it is safe and effective for widespread use.

WHO has prequalified four TCVs and two are eligible for introduction support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi). Once a country has an approved Gavi application and begins to plan a campaign, these vaccines are ready to be manufactured in bulk and shipped to the country as refrigerated cargo.

Countries examine many factors when deciding whether to introduce a new vaccine. Data on typhoid burden, including drug resistance, and cost-effectiveness can help inform countries’ decision-making about TCV introduction. In Malawi, a 2024 study found that introducing TCV alongside measles-rubella and polio vaccines likely cost less than conducting a standalone campaign. Evidence on cost-effectiveness can help inform future immunization campaigns, along with other countries’ decisions about vaccine implementation.

Transportation and storage

Making a vaccine is one thing—but moving it is another. Once vaccines are manufactured, they must be kept in a specific temperature range until the moment of vaccination to preserve their potency. Countries must maintain a precise network of temperature-controlled environments to transport and store the vaccines, known as a cold chain. The cold chain needs to extend across the country and throughout transport, in urban and rural areas, and hard-to-reach locations to ensure viable vaccines are distributed country-wide.

While the vials and other materials required for TCV may seem small, they add up—Burkina Faso’s recent TCV campaign, for example, reached more than 10 million children. Launching a large-scale immunization campaign requires huge warehouses and cold storage facilities where countries can hold millions of doses before they’re distributed more locally.

Distribution and delivery

Maintaining the cold chain can be a challenge during TCV introduction and routine immunization, as many typhoid-endemic countries have warm or tropical climates. In Malawi, temperatures can reach 30oC to 35oC during the warmer months, while TCVs must be kept between 2oC and 8oC. To keep vaccines cool, health care workers use specialized shipping containers and temperature-monitoring devices that alert them to temperature changes. New technology like solar-powered refrigerators can also help preserve vaccines in areas without a reliable power supply.

From central storage facilities, vaccines are shipped to regional storage facilities and then distributed to local communities—whether by car, motorcycle, bicycle, on foot, or even with multiple modes of transport. The cold chain must be preserved throughout each of these steps.

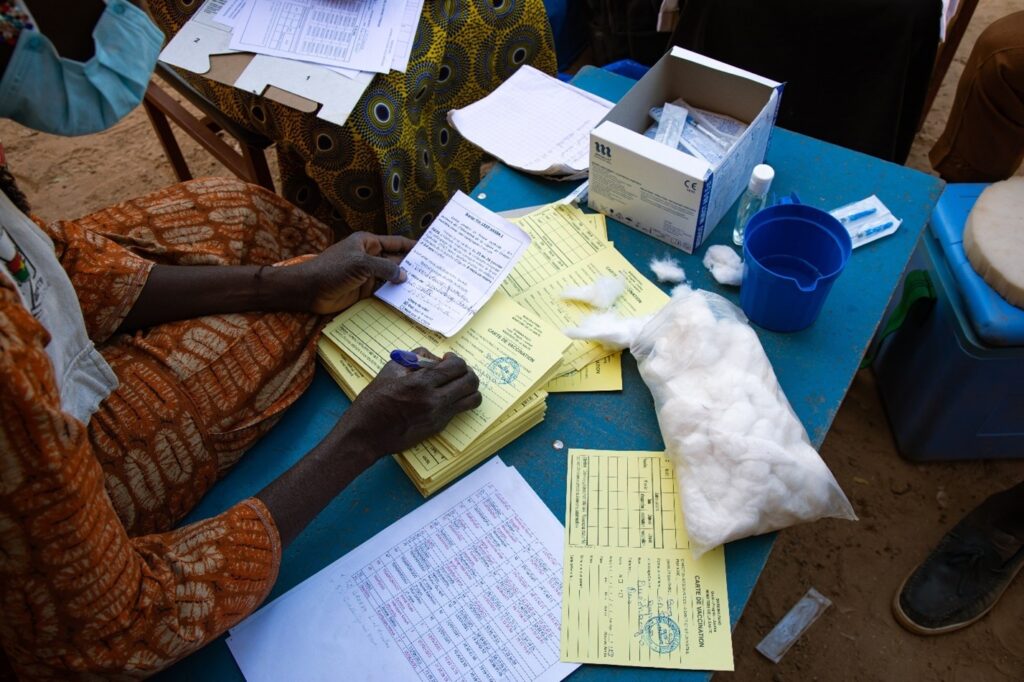

During a TCV campaign, health care workers administer TCV—which are suitable for children 6 months of age and older—at health facilities, schools, places of worship, and other fixed and mobile sites across the country. Following the campaign, TCV are available at health facilities during routine childhood visits. TCVs provide safe, durable protection from typhoid for at least four years.

TCVs can be safely administered alongside other routine vaccines, such as measles-rubella, meningococcal A, polio, and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. Malawi introduced TCV in 2023 as part of a campaign that also provided vaccines for measles-rubella and polio, as well as vitamin A supplementation. In 2021, Zimbabwe introduced TCV with a campaign that integrated TCV with the inactivated polio vaccine and HPV vaccine.

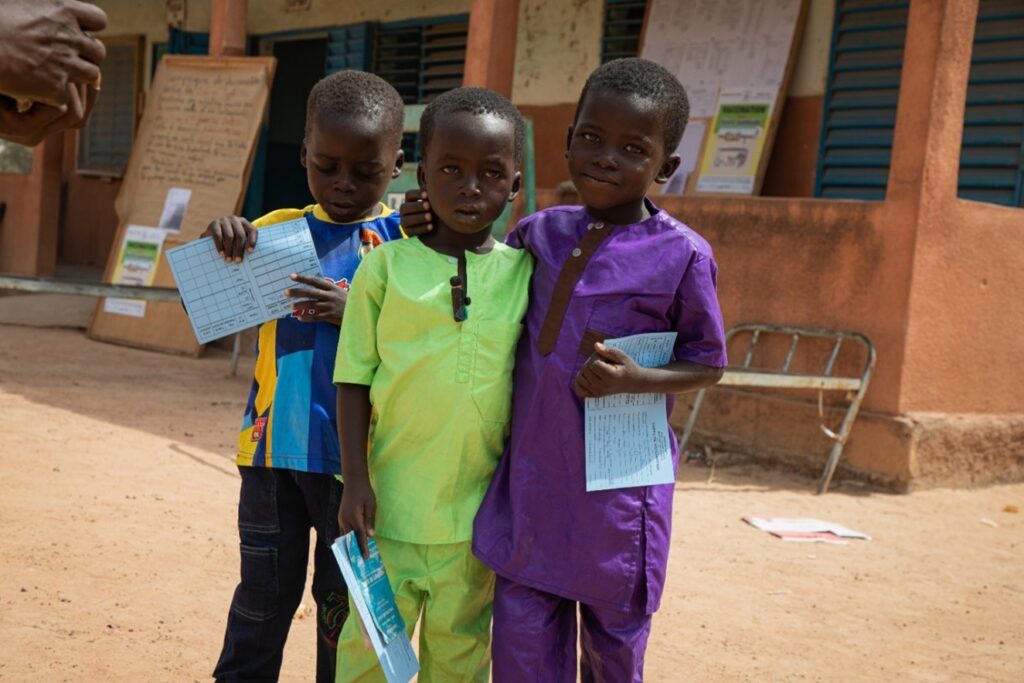

Monitoring and evaluation

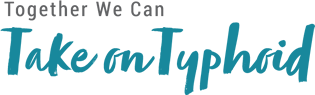

As the vaccines are administered, health care workers record data on vaccination cards and tally sheets. Coverage data help countries evaluate the future reduction in disease burden and develop plans to reach children who were not vaccinated during the campaign.

A health care worker fills out vaccine cards during an immunization campaign in Burkina Faso. Credit: TyVAC/Build Africa Communications

Cleanup and disposal

Once administered, used TCV syringes are placed in secure boxes for safe disposal. The boxes are taken to designated facilities for destruction through incineration, autoclaving, or another method of approved waste management. Since introducing a new vaccine can lead to a significant increase in the volume of used injection material, WHO recommends that countries assess their waste management needs prior to vaccine introduction.

While the lifecycle of a TCV ends here, its legacy is substantial. Every dose of TCV provides long-lasting protection against typhoid, and more than 75 million children have been vaccinated with TCV through introduction campaigns to date. This success depends on effective communication and social mobilization in communities to build trust, dispel myths, and increase vaccine acceptance. Vaccines cannot save lives if they sit on the shelf; encouraging caregivers to bring their children for vaccination is as essential as maintaining a reliable cold chain.

It takes hard work and commitment from dozens of stakeholders and partners, including community members, to bring each vial, syringe, shipping container, and cooler where it needs to be, but the ultimate destination—typhoid prevention and control—is a place well worth going.

Cover photo: An immunization campaign worker carries a cooler of typhoid conjugate vaccines in Burkina Faso. Credit: TyVAC/Build Africa Communications