Timothy Mutuma has been working as a research assistant for the past two years, balancing his time between the clinics in the informal settlements of Mbagathi and Mukuru and the lab at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) in Nairobi. His research has been underway since 2013, testing samples from children under the age of 16 for typhoid. Generally, any child with a fever is recruited to the study as a possible case. “Sometimes you can be a carrier without showing symptoms,” Timothy said. Since they have started this approach, more cases of typhoid have been identified than in the past.

Timothy explained that the number of typhoid cases he sees depends on the season, especially in the crowded informal settlements, which have few covered sewer systems and are prone to flooding when it rains. “When it rains it’s not a good place to be,” he said. “When there is a lot of rain the number of cases will increase.” On average, they’ll bring ten to fifteen samples back to the KEMRI laboratory for testing each day. The whole process of testing the samples and communicating the positive results to the patients usually takes about five days, which is all free of charge.

Timothy says that the largest issue in the study is getting people to follow up after they have received the medication. “You have to be very patient with your patients,” he explained. “After the patient has completed their treatment, getting the kid to follow up is difficult.” Timothy wants to make sure that the treatment has worked and that the patient is in fact negative for typhoid. This follow-up test is usually given two weeks after the treatment has been completed. At the KEMRI laboratory, preliminary results reveal that more than half of the typhoid cases are resistant to at least three types of medications commonly prescribed to treat typhoid. A multidrug-resistant typhoid strain called H58 has emerged and spread in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, possibly responsible for the many drug-resistant samples seen in the KEMRI laboratory.

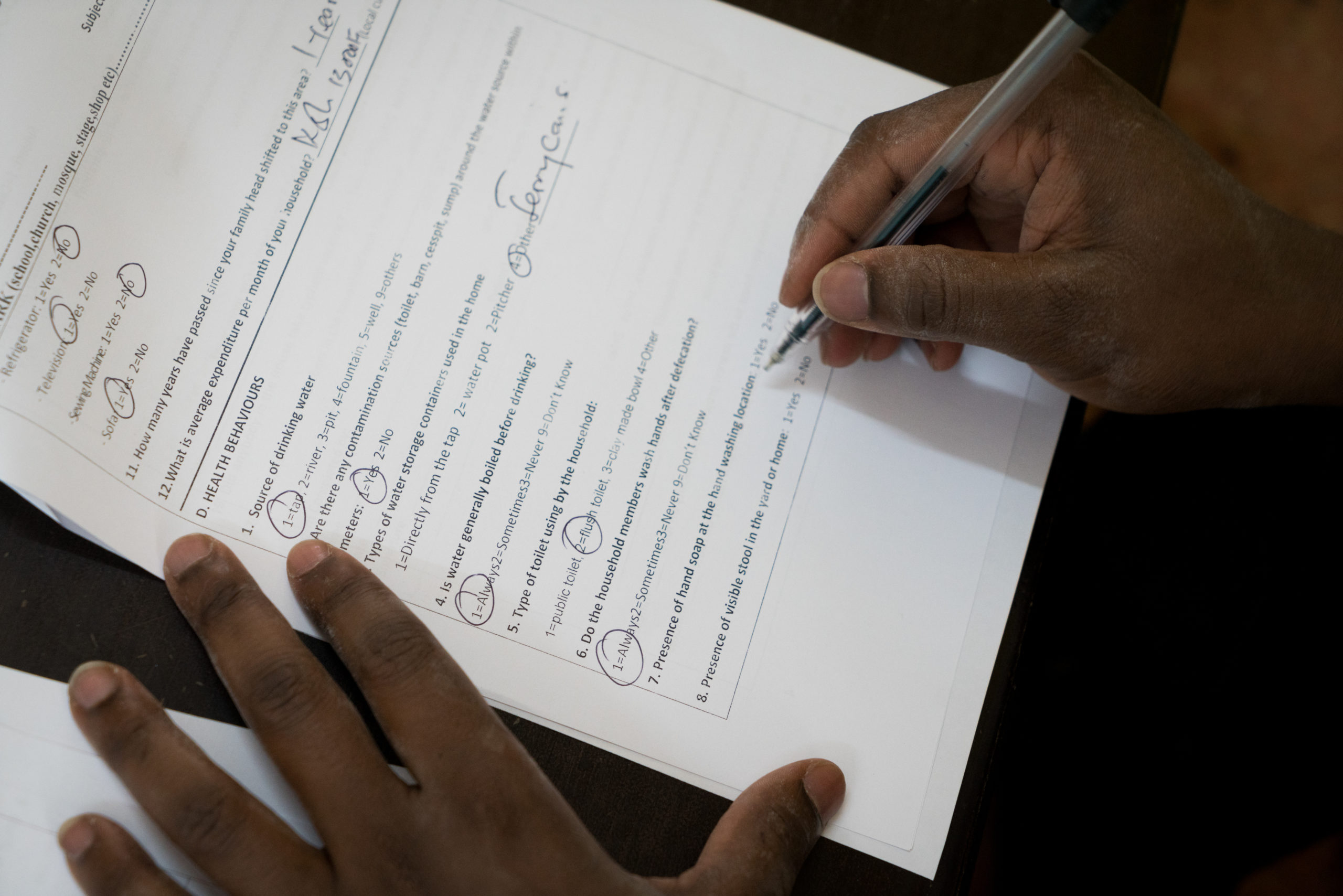

Besides collecting and processing samples, Timothy also administers questionnaires to glean a better understanding of patients’ water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practices at home, including sources of water and food, how drinking water is treated and how food is prepared, and what type of latrines are used. The results of the questionnaire are then used to inform community health workers (CHWs) who visit the homes of the patients to ensure that the household practices will not contribute to more sickness in the future. This coordinated teamwork between the lab staff and CHWs represents important efforts to reduce the spread of typhoid in these informal settlements.

Typhoid vaccines have not been accessible to people in the informal settlements where Timothy works, mainly because they are not subsidized by the government. The Kenyan government provides most other vaccines free of charge to children under the age of five. Timothy believes that the cost of the vaccine is the one factor that is stopping people from receiving it. “If the typhoid vaccine was available alongside other vaccines, people would be very willing to take them,” he said. While not yet available globally, typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs) show great potential to provide longer-lasting protection to children younger than two years of age. Because TCVs can be administered to children beginning at six months old, they have the potential to be integrated into routine childhood immunization schedules, like Timothy suggests.

Photos and reporting courtesy of ©Sabin Vaccine Institute/Adriane O’Hanesian. This post is part of Stories of Typhoid, a series sharing the impact of typhoid on families and communities in endemic countries.