Frontline healthcare workers—physicians, nurses, laboratory personnel, community health workers (CHWs), and social mobilizers—confront typhoid in their communities every day, and therefore have an integral role in typhoid prevention and control. During the 11th International Conference on Typhoid and Other Salmonelloses we celebrated a few of these exemplary healthcare workers and the many ways each of them is working to take on typhoid. Now, we are pleased to share their work and highlight the impact each is having in their local community in our four-part blog series, “Prevention in Action.”

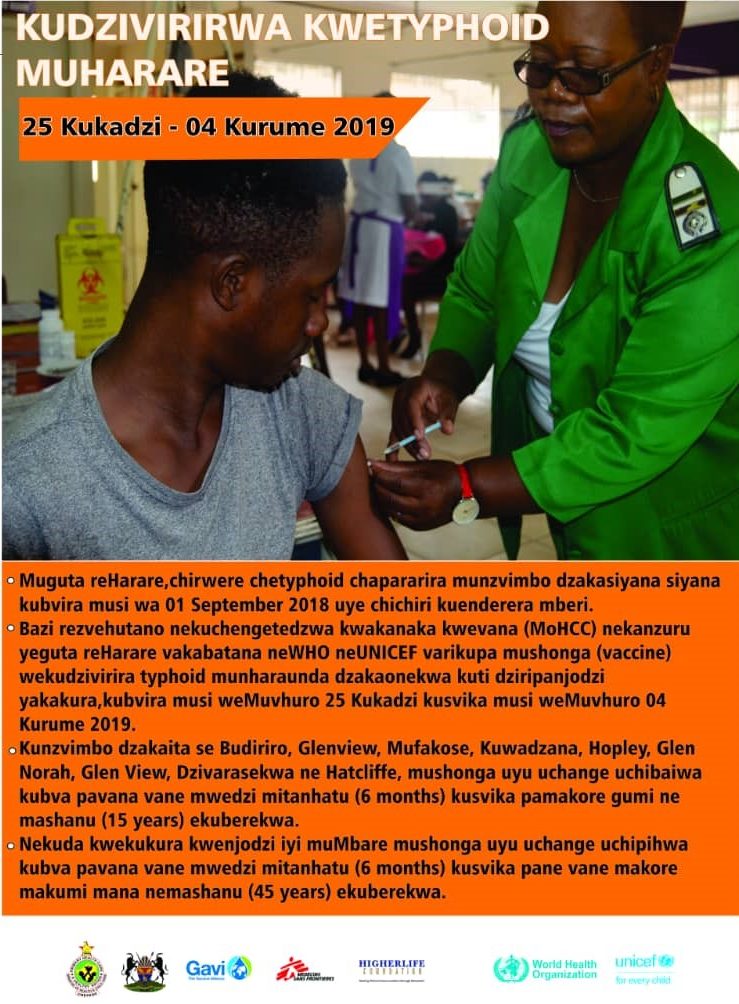

We close this series with Sister Pricila Mkahanana, the Sister in Charge at Mbare Poly Clinic in Harare, Zimbabwe who oversaw the mass typhoid vaccination campaign in Harare from February 22-March 4, 2019. This is her story.

—

As a young child I always looked forward to visiting my local health clinic in rural Zimbabwe. While many of my peers feared the pokes and prods, I enjoyed my visits, wide-eyed and intrigued by the physicians and nurses who saved peoples’ lives and their gadgets and tools that helped them to do so. Even when receiving my vaccinations—a scary endeavor for many young children—the nurses in their all-white uniforms appeared to me like guardian angels, their smiles and kind demeanor putting me at ease. From a young age, I knew that I, too, wanted to be a nurse. I focused on this dream throughout my years in school, and with the help and support of my family, I eventually earned a postsecondary diploma in nursing.

Today, as a nurse at Mbare Poly Clinic—a high volume urban health facility serving a population of 92,565 people—I try to offer the same compassion and quality care that I received in my local clinic when I was a child. Located in one of the oldest suburbs on the outskirts of the capital city, Harare, the clinic primarily serves an impoverished community that is characterized by overcrowding and poor sanitation infrastructure, predisposing many to disease, including typhoid.

As the Sister in Charge, I oversee and manage the Family Health Services department with the help of six trained nurses, two nurse aids, and one cleaner. Through health education, family planning, HIV-prevention, growth monitoring and immunizations, we aim to keep the families of the Mbare community healthy. On most days, demand for our department’s services far exceeds the supply, but we do our best to see and treat as many patients as possible.

Typhoid is a common culprit behind many of our patients’ symptoms, impacting both children and adults alike. Because of a lack of sanitation infrastructure, city-wide water rationing, poverty and crowded conditions, typhoid spreads easily and quickly through our community, which experiences outbreaks on a near annual basis. This not only strains the resources of the clinic as staff experience burnout, but it also causes great economic and development setbacks for the community. For example, wide-spread absenteeism of staff and pupils in school is often reported during outbreaks, causing students to miss valuable lessons and fall behind in their studies. Further, many households lose much-needed wages when their primary breadwinner is either hospitalized due to infection, causing enormous stress on families as they try to cope with both a sick loved one and financial instability.

Despite the significant burden that typhoid places on the people of Mbare, preventive interventions have largely focused on drinking and cooking with clean water and handwashing with soap. While these interventions are recommended as part of any integrated prevention programming, they often are not enough to keep young children adequately protected against typhoid. Our last defense is often post-infection treatment with antibiotics. However, the rise of drug-resistant strains presents new challenges to this approach; approximately one in five cases of typhoid in Harare are estimated to be resistant to first-line antibiotics, with an alarming 73% resistance reported in certain areas.

These factors helped influence the recent decision by Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Health and Child Care—with support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the World Health Organization, and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—to introduce the new typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) as part of the response to a major typhoid outbreak that began in September 2018. Given my close familiarity with the community and prior experience managing mass immunization campaigns, I was appointed to oversee the community health awareness and immunization campaign—the first non-trial TCV campaign in Africa. What did this look like?

In the four weeks leading up to the start of the campaign, we enlisted 110 trained health workers, including nurses, who had prior experience and exposure to immunization campaigns and programs, and had familiarity with the nine suburb communities that were part of the campaign. We split the trained health workers into 10 teams and conducted a Training of Trainers workshop with each team supervisor, who then trained the health workers that would be part of their suburb’s campaign. In the midst of training, we also procured all of the necessary resources and made sure that the cold chain management system was in place and well understood by all staff.

As the campaign start date neared, we deployed social mobilizers throughout the suburbs to disseminate information and raise community awareness of the campaign. We held meetings with various community and political leaders to ensure wide-spread buy-in and support from the community at the highest levels. This was particularly important because of the misinformation about vaccines that can quickly spread throughout communities. Because we anticipated this and proactively worked to engage community leaders, we faced very few objections from the community and were able to overcome the small percentage that had misgivings.

Once the campaign began, my team of supervisors and I provided oversight on a daily basis, visiting each team and checking for proper documentation, cold chain maintenance, and operations at each campaign site. We kept morale among the teams high at our morning debriefings, where we would site the previous day’s statistics, give praises and recognition of outstanding team members, and provide encouragement to reach the coming day’s target.

Through the course of just eight days, from February 22 – March 4, 2019, the campaign vaccinated 318,662 Harare residents! This campaign was an overwhelming success, largely due to the in-depth and comprehensive planning, design, and coordination of the campaign; the widespread community buy-in and enthusiasm; and the dedication and hard work of the trained health workers and social mobilizers involved.

While the campaign may now be over, the benefits of TCV will be felt across Harare for many years to come. I feel comforted by the fact that we managed to protect so many people from future typhoid infections, especially in my community of Mbare. As countries consider introducing TCV into their routine immunization schedules, I hope that they can learn from the success of this campaign and realize the live-saving potential of this new vaccine.

Photos courtesy of Sister Pricila Mkahanana.