In South Asia, where the burden of enteric fever is thought to be highest, most typhoid studies have focused on urban areas. As a result, researchers have been unsure how well available data could be extrapolated to predominantly rural areas.

In Nepal, where more than 80 percent of the population is rural, a new study investigated typhoid outside of major cities. The research, conducted at Dhulikhel Hospital, one of the Sabin Vaccine Institute’s partners in the Surveillance of Enteric Fever in Asia Project, is among the first to look into the burden of typhoid in peri-urban and rural Nepalese populations.

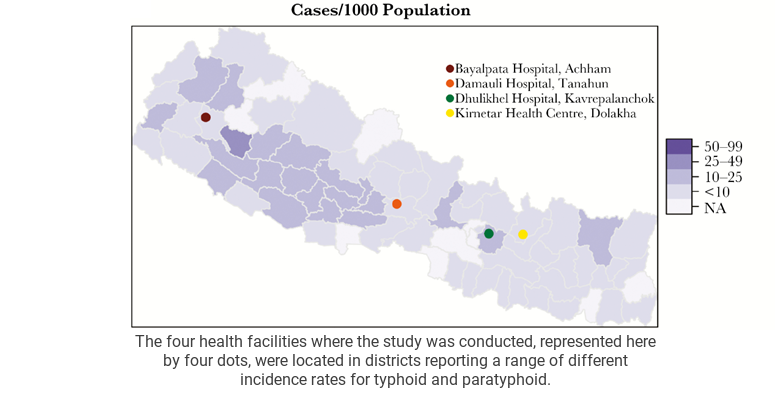

The study, which took place at four health facilities in different parts of Nepal (see the map above) found that typhoid is the most common empirical diagnosis – diagnosed by a doctor based on symptoms – among patients who have had a fever for longer than three days. Of these patients with an empirical diagnosis of typhoid, however, only 4.1 percent of cases were confirmed by a blood culture test, the most accurate way to diagnose typhoid. Based on these results, researchers estimated that more than 90 percent of patients empirically diagnosed with typhoid in peri-urban and rural areas did not actually have any form of enteric fever.

These findings indicate that the majority of patients diagnosed with typhoid fever may not be receiving effective treatment for their condition. Medications prescribed incorrectly are often ineffective, and may prolong illness compared to the correct treatment. Incorrectly prescribed medication can contribute to antimicrobial resistance. As antimicrobials are used more frequently, pathogenic bacteria gain more opportunities to develop resistance to them. Antimicrobial-resistant infections require the use of more costly medications and threaten a doctor’s ability to treat common infections, including typhoid.

This data on typhoid burden in peri-urban and rural Nepal also highlights differing patterns of typhoid between rural and urban populations. The study found that positive blood culture tests were strongly correlated with population density, meaning that urban dwellers in Nepal were more likely to actually have culture-confirmed typhoid than rural Nepalese.

As the new typhoid conjugate vaccines move closer to introduction, it is now more important than ever to understand how best to utilize vaccines to prevent typhoid. Typhoid conjugate vaccines offer protection that is more complete, longer lasting and safer for young children than currently available typhoid vaccines. If approved for distribution in a vaccination campaign, these vaccines could make a vital difference in the prevalence and severity of typhoid in Nepal, and more accurate data would help the government identify the most efficient and cost-effective ways to utilize them. Understanding the true distribution of typhoid fever in a population – not only the fraction that live in cities – is crucial to any vaccination strategy.

The research conducted at Dhulikhel Hospital will help inform the second phase of Sabin’s typhoid surveillance project as we continue to investigate typhoid burden in Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Sabin’s project in Asia will provide a greater understanding of where and how people contract typhoid, and therefore how best to stop it, whether in the cities or the countryside.