Meet Suzen, a 20-year-old information technologies (IT) student in his second year at college in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Outside of school, Suzen works at his family’s jewelry store and plays football with his friends.

In May, with exams approaching, Suzen started to feel sick with a high fever. After two days of fever, Suzen went to the pharmacy and bought paracetamol in an attempt to reduce his fever. Instead of improving, his fever worsened and he developed headaches, stomach aches, vomiting and body aches.

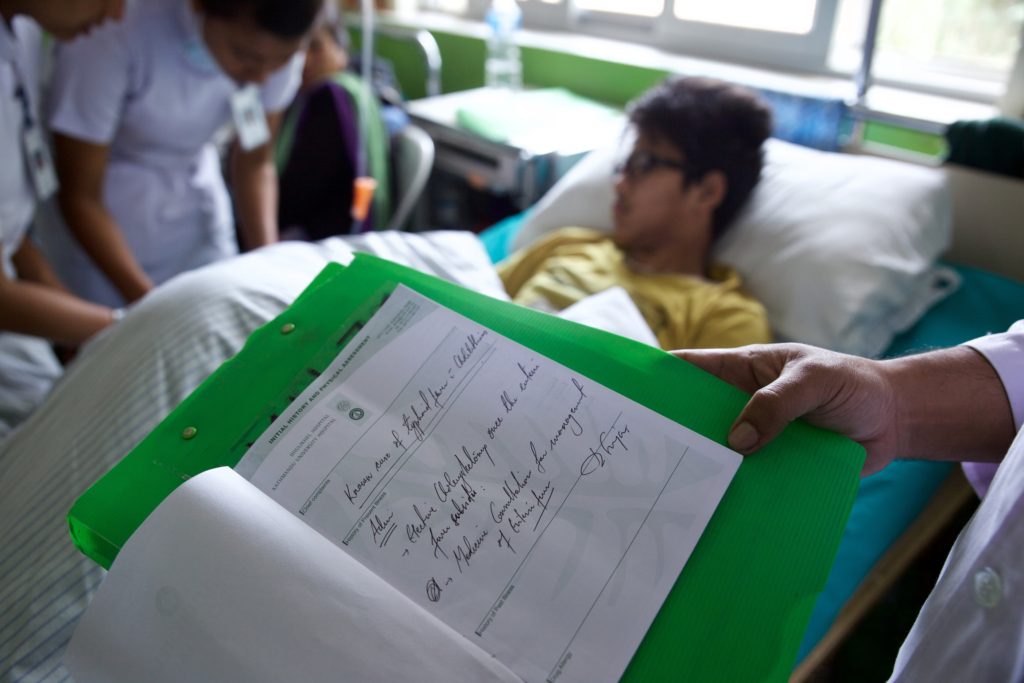

After 10 days of unrelenting sickness, Suzen went to Bhaktapur Hospital where he was admitted for blood tests. The tests confirmed that he did not have a typical seasonal flu, but typhoid fever. With his diagnosis, Suzen was transferred to the larger Dhulikhel Hospital 20 kilometers away where it was believed he could receive better treatment. Upon his admittance, his temperature was 104°F (40°C).

High fevers like Suzen’s are a trademark of typhoid, a disease transmitted through contaminated food and water that causes approximately 200,000 deaths annually. Ninety percent of these deaths occur in Asia. In highly endemic countries like Nepal, where studies have shown municipal water sources are a reservoir for the bacteria causing typhoid, prevention in key.

A typhoid vaccine is currently available, but is mainly targeted to foreign travelers and not families living in low-resource areas like Suzen’s. This may soon change. A new typhoid conjugate vaccine is in development and could be available to those most at-risk by late 2017.

Typhoid can also be prevented by avoiding contaminated food and water. Suzen has always been careful to drink filtered water, but is now second guessing his eating habits. “I had chat-pat a day or two before I had fever. Also, I ate cut watermelon from the fruit shop on the street,” he said. Either of these foods could have been the culprit, as watermelon and chat-pat, a snack sold by street vendors, are not cooked, putting them at risk for bacterial contamination.

Suzen was plagued by pain and weakness throughout his hospital stay, and was unable to work or prepare for his exams. After five days, he was discharged from Dhulikel and returned to his family home, which was heavily damaged by the earthquake that struck Nepal in 2015.

Suzen’s illness was a setback for his family, who are living on the first floor of their house as the top floors are too damaged for habitation. “We need to break down our house, so we can rebuild. But we will need to take a loan for that, hence we are still living in this damaged home,” said Suzen’s sister, Hasna.

Three days after he was discharged, Suzen was fever-free, though still suffering from stomach problems. Despite the costs of typhoid to Suzen and his family, he was lucky – because he has access to quality medical care, this deadly disease became an obstacle to overcome, not a dead end.

Typhoid most often affects the poorest, who may not have access to a hospital or even a blood test to identify the disease. And even for those like Suzen who survive, the economic costs of typhoid are enormous. In 2010 alone, Typhoid cost the world an estimated $1 billion in lost productivity. But this can be prevented. With affordable vaccines and clean food and water, millions could avoid typhoid.

Reporting and photos by Mithila Jariwala. This post is part of Stories of Typhoid, a series sharing the impact of typhoid on families in endemic countries.