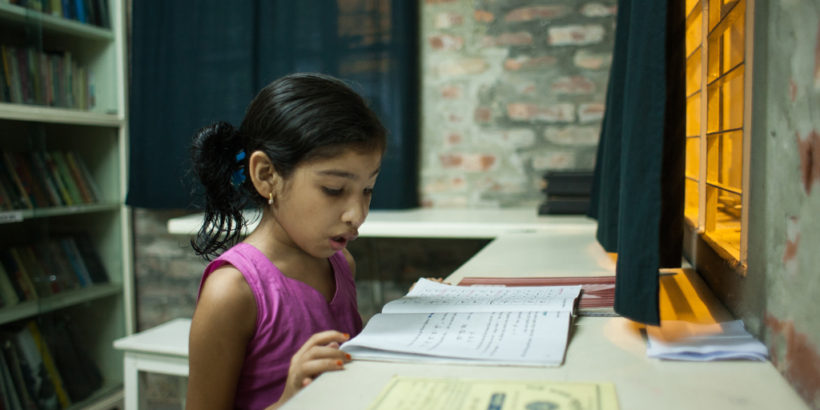

Meet Nishita. A nine-year-old who wants to go to school so badly that she reads her textbook, by herself, by the light of the window in her family’s house. But this Bangladeshi third-grader hasn’t been able to go to class since she contracted a severe case of typhoid.

Nishita spent more than a week burning with a fever of between 102° and 104° Fahrenheit. Instead of taking her school tests, she has been struggling to hold down food and water in the face of her sore throat, stomach pains, constipation and bouts of vomiting.

With a limited household budget, her parents, Motiar and Rehana, hoped that Nishita would get better with doses of Paracetamol, a common pain and fever reducer. But the over-the-counter medication only provided a brief respite. Only a few hours after each dose, her fever would return to dangerously high temperatures. After a week, as Nishita steadily became weaker, her alarmed parents rushed her to the doctor.

Several days of being unable to swallow or keep down water had left her badly dehydrated, on top of her other symptoms. But as Nishita lay on the hospital bed, receiving an intravenous drip of saline solution, she mostly thought about the classes she was missing.

“I love to go to school,” she explained. “I wonder when I will start going to school again?”

While at the hospital, Motiar and Rehana learned that the mysterious illness plaguing their daughter was not the standard viral fever they originally suspected. A blood test confirmed that Nishita had typhoid, a disease relatively unknown to them.

She might have contracted it from eating contaminated street food—that’s her parents’ best guess. But typhoid fever is endemic in Bangladesh, and where typhoid is endemic, children are always the ones most at risk. Most of the 22 million cases of typhoid each year affect children, who have little control over the environments they play and live in, whether the food they eat is contaminated, or whether their water is clean.

All over the world, children miss a total of 443 million school days due to waterborne diseases like typhoid. These missed school days do not only impact the child’s future, but a country’s economic growth. Research demonstrates that for every 10 per cent increase in female literacy, a country experiences 0.3 per cent economic growth. Nishita’s missed school days matter to Bangladesh.

Research has also shown that typhoid vaccines can help protect at-risk children like Nishita. In Guilin, China, one of the few places to have implemented a systematic typhoid vaccination program for school-age children, the incidence rate of typhoid in students dropped by 92-99% in the years following vaccination. The evidence is clear that typhoid vaccination for school-age children can nearly eliminate the threat of typhoid in endemic areas.

Nishita is now well on her way to recovery. Under the care of her doctors, she has received rehydration therapy, a diagnosis, and antibiotics (which, like a typical nine-year-old, she dislikes taking). Her appetite is starting to come back, and soon—although perhaps not soon enough for Nishita—she will get to go back to school.

Reporting and photos by Suvra Kanti Das. This post is part of Stories of Typhoid, a series sharing the impact of typhoid on families in endemic countries.