Meet Asim Shrestha. As a practicing pediatrician in Dhulikhel Hospital in Kavre District, Nepal, Dr. Shrestha is all too familiar with the story of typhoid. A steady stream of children pass through his ward, sick with the disease.

“Kids generally pick it up after 2 years of age,” said Dr. Shrestha. “Usually the kids who come here are four to five years of age and above. Patients who come here are from villages; in most cases, low to middle income families.” Often, these families have the most trouble paying for typhoid treatment when a loved one becomes ill. While typhoid vaccines are available, these families also find it difficult to access and pay for them, so they are caught in a bind, gambling on the chance that none of their children will contract this debilitating disease.

One of the children caught up in that gamble was Dr. Shrestha’s latest patient, a 13-year-old boy named Subigyan Khanal, who was complaining of high fever, weakness and headache. Subigyan, who is from a nearby village, should have been enjoying his summer vacation. Instead, just as the school break began, he came down with a fever.

“We don’t know what happened to him,” said his older brother, Subhash, who accompanied him to the hospital. “We drink boiled water, he eats cooked food at home.”

Typhoid is most often transmitted through contaminated water or food, so drinking boiled water and eating food prepared at home, rather than on the street, lowers the risk of contracting typhoid. In countries like Nepal, however, where typhoid is highly endemic, the danger of typhoid is widespread and not easily avoidable.

Subigyan told Dr. Shrestha that he had tried to recover on his own, but he did not get better with rest. Over the course of a week, his fever rose to 104 degrees Fahrenheit. At one point, according Subigyan, he went to a local treatment center where he received medicines that had almost no impact on his fever. It’s a version of a story that Dr. Shrestha hears often. It is not uncommon for the patients he sees to buy medicines before receiving a diagnosis or even consulting a doctor at a hospital.

But these medicines don’t tend to work well on typhoid patients. This is because, Dr. Shrestha explained, often the medicine given is incorrect. Typhoid’s flu-like symptoms are easily mistaken for malaria or pneumonia leading to misdiagnosis or a delay in correct treatment. To confirm a case of typhoid, a laboratory diagnostic test is needed.

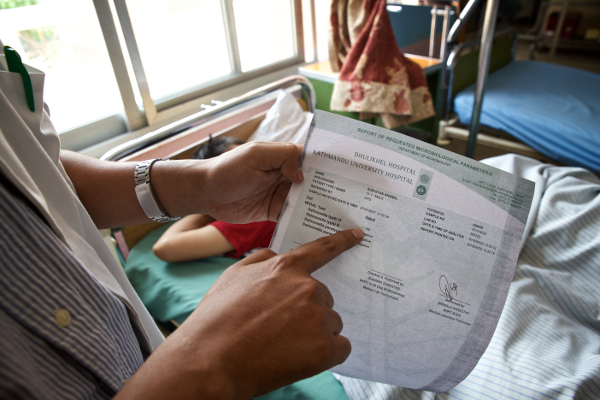

When Dr. Shrestha first met Subigyan at his clinic, he quickly suspected that Subigyan had typhoid fever. But there was a complication: two different typhoid diagnostic tests gave two different results. While Subigyan’s blood culture test came back negative, his Widal test came back positive.

According to Dr. Shrestha, this is another common complication in diagnosing and treating typhoid. The blood culture test, while the best option for many doctors in typhoid-endemic areas, is only able to detect 40 to 60 percent of cases. It is particularly difficult to use with younger patients, as the amount of blood required for the most accurate reading is difficult to draw from children. To make matters worse, taking medication before a blood culture — as Subigyan did — can lower the accuracy of the test. Based Subigyan’s low white blood count and the typical symptoms of typhoid, Dr. Shrestha made the decision to treat Subigyan for typhoid.

Doctors in typhoid endemic areas who are working with limited resources and time often must make these kinds of difficult decisions. All of the typhoid diagnostic tests that are currently available have serious limitations, but a delay in treatment increases the chance of a patient developing severe typhoid complications. Doctors like Dr. Shrestha must simply do the best they can based on their experience and knowledge, and hope for something better. For Dr. Shrestha, that hope rests in the form of vaccines.

“I think it is required to make [the] typhoid vaccine mandatory,” he said, strongly urging prevention in favor of treatment. “Especially during the epidemic time, which is summer. It is not mandatory in Nepal, but it should be. It will reduce the number of patients.”

There are currently two licensed vaccines available for typhoid, both of which have been proven to be safe and effective. These vaccines, however, are out of reach for average Nepalis, and typhoid isn’t included in any national immunization campaigns. The new typhoid conjugate vaccines in development look to be even more effective than the vaccines currently available and will likely be approved for release in the next two years. These upcoming vaccines represent a new chance to persuade governments of typhoid-endemic countries like Nepal to vaccinate their populaces for typhoid.

Vaccines can provide the difference in fighting this disease, especially when doctors like Dr. Shrestha only have access to imperfect diagnostic tools. By making vaccination against typhoid widely available and administered to the public, children like Subigyan can avoid ever experiencing the debilitating symptoms of typhoid in the first place.

Reporting and photos by Mithila Jariwala. This post is part of Stories of Typhoid, a series sharing the impact of typhoid on families in endemic countries.