In September, I traveled with colleagues from Sabin Vaccine Institute to Pakistan to observe ongoing typhoid surveillance and control activities. Pakistan is a country with a well-documented history of typhoid fever endemicity,1,2 and recent data indicate that 50% of strains are multi-drug resistant (MDR), or resistant to first-line antibiotics (chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ampicillin/amoxicillin) and more than 90% of strains are resistant to fluoroquinolones.3 In November 2016, the Aga Khan University (AKU) hospital reported an outbreak in Hyderabad caused by an extremely-drug resistant (XDR) typhoid strain, which also exhibited resistance to ceftriaxone.4 Since that time, the outbreak has spread to Karachi, where several thousand cases of XDR typhoid have been reported.

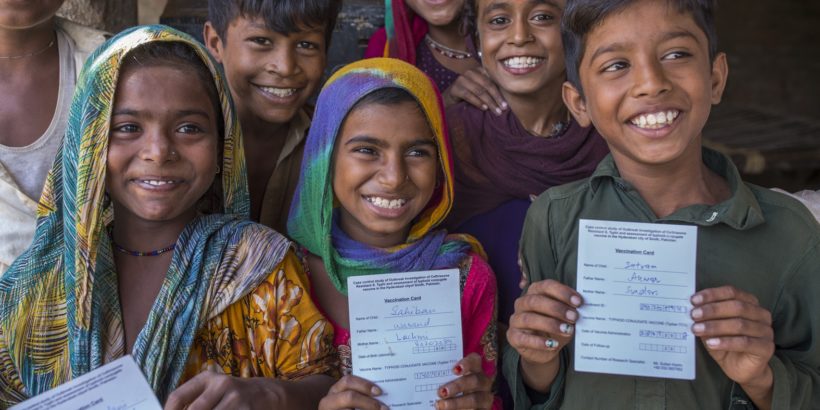

While in Pakistan, I visited Kharadar General Hospital (KGH), one of the Surveillance for Enteric Fever in Asia Project (SEAP) sites in Karachi, where mothers and children had been queuing for hours. Free typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs) were being distributed and these mothers wanted their children to be protected. The perceived need for TCVs in this community is great. KGH serves one of the communities most affected by the XDR outbreak in Karachi, which also happens to be among the poorest and most densely populated.

Unfortunately, TCVs did not arrive in time to protect all children. One such child was six-year-old Muhammad, who was admitted to KGH with typhoid. While typhoid patients can be typically be treated with antibiotics as outpatients, cases of XDR typhoid have reportedly resulted in longer hospital stays and may lead to increased risk of mortality, particularly for those children who are unable to receive treatment in a hospital or clinic. Currently, azithromycin is the only reliably-available first-line oral treatment option to treat XDR typhoid, raising fears that “untreatable typhoid” may become a grim reality soon.5

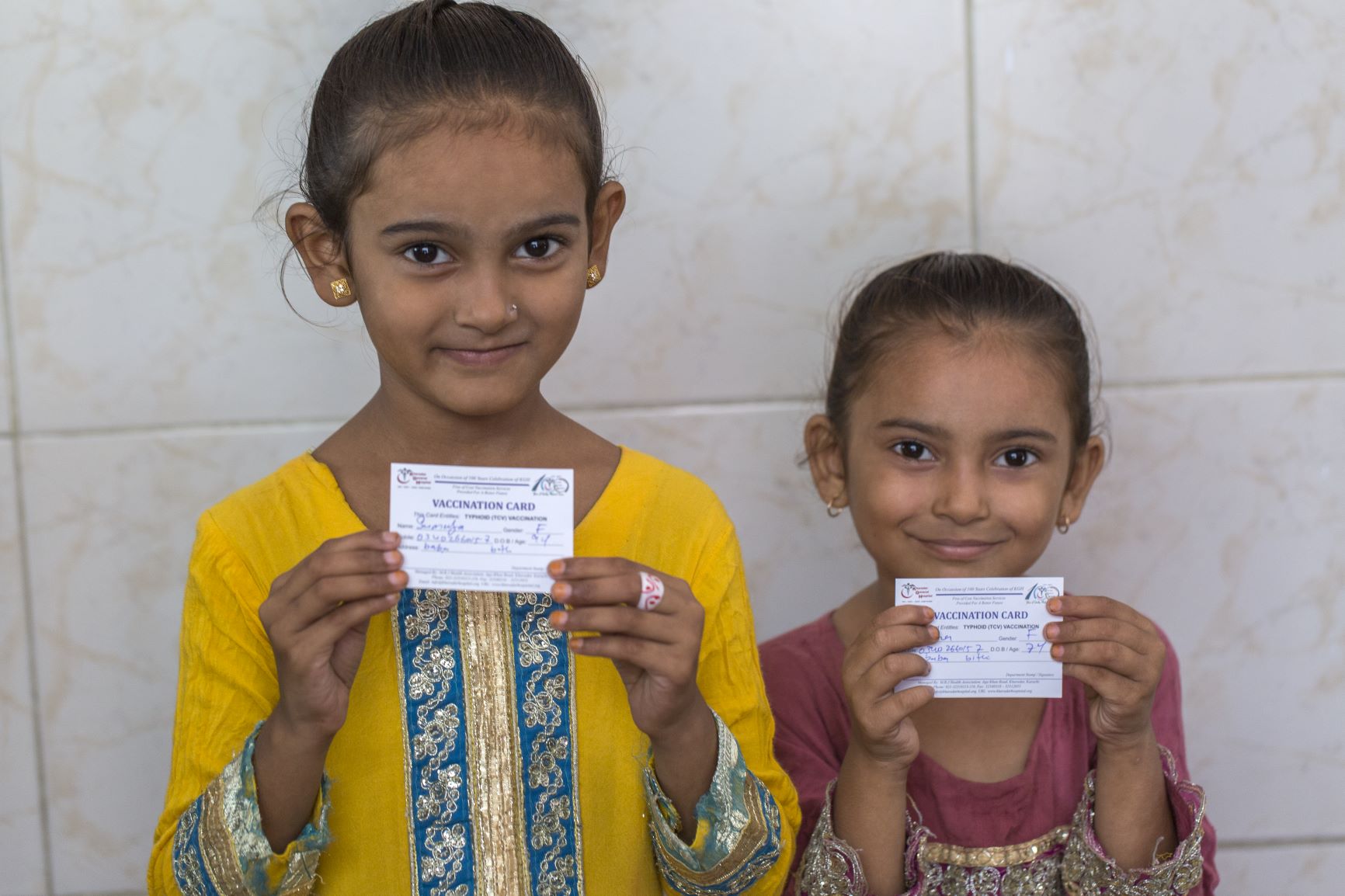

We also traveled to Hyderabad, where AKU is conducting a door-to-door vaccination campaign. Community mobilizers visit households in the neighborhoods of Latimabad and Qasifabad to speak with families about the threat of XDR typhoid and the important role of TCVs in preventing this serious illness. Shehnaz Behgum was at home with her three-year-old grandson, Arham. The community mobilizer was able to answer Shehnaz’ questions about typhoid and TCVs and direct her to a mobile vaccination unit parked at the end of her street. Arham was taken to be vaccinated and now is protected against the outbreak occurring in his city.

I also had the chance to celebrate an important milestone in the TCV response to the XDR outbreak in Hyderabad with a large and enthusiastic team of community health workers, vaccinators, logisticians, clinicians, and researchers. This event marked 100,000 doses of TCV being delivered as part of the response to the XDR outbreak in Hyderabad, the first TCV outbreak response of its kind. This effort will generate important data about vaccine performance and operational feasibility in an outbreak setting. This dedicated team will go on to vaccinate a total of 250,000 children in an effort to contain the dangerous outbreak. The team is also implementing water, sanitation, and hygiene, and health education interventions in these communities as part of an integrated control approach.

These important efforts in Karachi and Hyderabad have the potential to be part of a longer term TCV implementation strategy in Pakistan. Given the significant burden of typhoid in other parts of South and Southeast Asia, as well as in sub-Saharan Africa, there is an important role for TCVs in global typhoid control today, particularly given the increasing threat of antimicrobial resistance. With a newly prequalified TCV, Typbar TCV®, and an open Gavi funding window, the time is now for countries to critically assess their typhoid burden and apply to Gavi for TCV introduction support.

Photo Credit: PATH/Asim Hafeez