Pour lire ce blog en français, veuillez cliquer ici.

For the past century we have witnessed remarkable gains in global health progress. Diagnostics and treatments, plus, vaccines and other health tools have led to an overall improvement toward longer, healthier lives.

We have also identified new or increasing challenges such as COVID-19, mpox, Ebola, and Marburg fever, that threaten to stall or reverse progress. Drug resistance, however, is a decades long challenge that is becoming increasingly worrisome. Globally, pathogens resistant to all-but-final line treatments are growing at an alarming rate. Consequently, we are now confronted by diseases that are more difficult and expensive to treat.

Typhoid and drug resistance

Drug resistance is having a negative impact on many communities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where typhoid is endemic. Typhoid caused nearly 7 million cases of illness and more than 93,000 deaths in 2021. It remains a serious, often underestimated, burden in many LMICs where improvements in water and sanitation infrastructure, diagnostics, and antibiotic stewardship are not keeping pace with population growth, movements, and other demands.

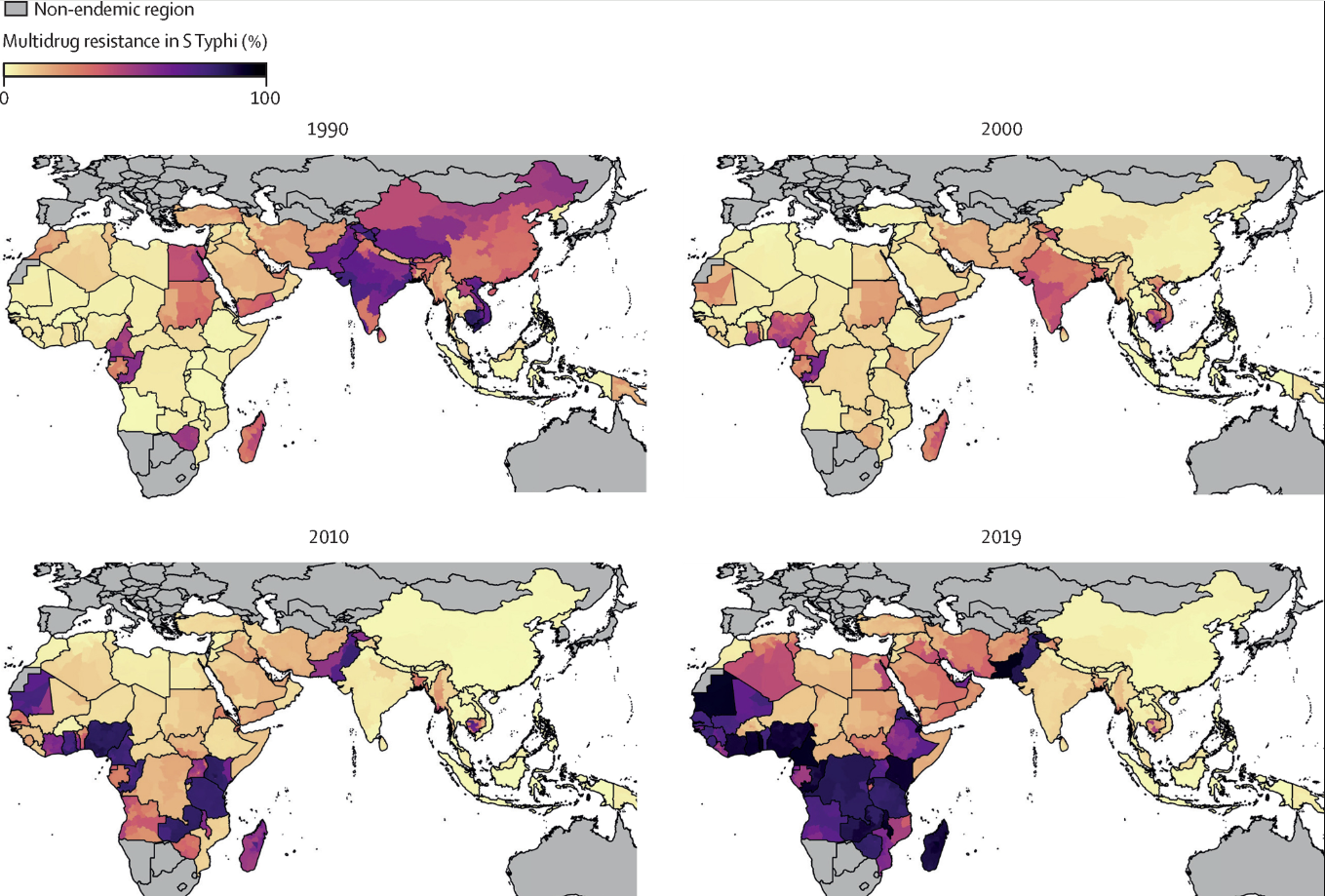

A modeling study from the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance Project, a partnership between the University of Oxford and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, estimates the overall number of drug-resistant and drug-susceptible infections per year. The comprehensive modeling framework includes more than 600 data sources.

The model shows global trends in drug-resistant enteric fever, revealing patterns in multidrug-resistant (MDR) typhoid that emerged in the 1990s and increased rapidly, accounting for more than 50% of all typhoid infections in 2019.

How did we get here?

MDR typhoid, defined as strains resistant to three first-line antibiotics, and extensively-drug resistant (XDR) typhoid, strains resistant to five classes of antibiotics, emerged over decades. Beginning in 1948, chloramphenicol was used to effectively treat typhoid, and while resistant cases were reported, they were not common. Between the 1950s and 1970s, new antibiotics were introduced, allowing for alternative treatment options when resistance arose. Subsequently, no crisis emerged as multiple treatment options were available.

By the 1960s, some cases of typhoid were showing multidrug resistance. In 1972, a large typhoid outbreak in Mexico showed MDR, but once this outbreak was controlled, only sporadic MDR cases were reported thereafter.

For the next two decades, diagnosis and treatment of typhoid continued, largely unchanged and unprioritized. The sense of urgency changed in the 1990s when fluoroquinolones, specifically ciprofloxacin, became the recommended treatment for typhoid in many settings because of treatment failures from increasing MDR typhoid cases. In the years following the switch to fluoroquinolones to treat typhoid, researchers observed reduced susceptibility to quinolones. Use of ciprofloxacin continued―and continues today―but with reduced effectiveness in many cases.

H58 and azithromycin resistance

Recent studies have shown that we are facing a predominant subtype of MDR typhoid called H58, of which many samples also show reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. The data show that more than half of typhoid isolates obtained to date belong to the H58 subtype, and that there are ongoing confirmed cases in both Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. For these cases, there are limited oral antibiotic treatment options, including azithromycin.

Azithromycin-resistant cases have been identified in Bangladesh, Niger, and Pakistan. These cases highlight the global crisis of drug-resistant typhoid. Diseases don’t respect borders, and drug-resistant typhoid anywhere is a threat everywhere. Reducing typhoid cases globally not only decreases the disease but also reduces antibiotic use, keeping existing drugs effective for those who must need them.

The time to act is now

While the current context of drug resistance emerged over time, we do not have the luxury of time as we work to control and prevent cases of drug-resistant typhoid. The existing data serve as an important resource for decision-makers considering the introduction of typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs) and highlight the need for improvements in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).

Data from Hyderabad, Pakistan, found TCV to be 97% effective against XDR typhoid. TCVs reduce the transmission of drug-resistant typhoid and reduce illness, which means an overall decrease in antibiotic use, especially in countries where blood-culture diagnosis is difficult. All policymakers, and particularly those in countries with a high burden of drug-resistant typhoid, have the information available from various sources to make informed decisions about the prioritization of TCVs. As treatment options for typhoid become more limited, a reduction in typhoid and subsequent antibiotic use is imperative.

We must work together in the fight against MDR/XDR typhoid. We must take what we know―and what we continue to learn―and harness the knowledge, data, and tools we have into integrated approaches for typhoid prevention and control.

Photo: A child waits with her mother to receive TCV during Zimbabwe’s introduction campaign. Credit: TyVAC/Kundzai Tinago.